This is the fourth and final episode of the summer Friendship Series. For the past month, I’ve taken a deep dive into friendship –– including the role friendship plays in our life; the ways in which culture influences friendship; and the gender dynamics in friendship. Today, I explore creative friendships.

Each theme includes audio interviews with over a dozen friends, as well as 7 sensory ways to explore friendship. For previous issues, visit The Friendship Series.

I made my first creative friendship on a full moon. I wouldn’t have known it, if he hadn’t scribbled “Look up” on his receipt. I had been too busy all evening –– head down, taking orders, running cocktails –– to notice the spotlight in the sky, shining like a projector over St Marks street.

I couldn’t have guessed that this stranger’s note was signaling a bigger change –– something to look forward to and someone to look up to. At that point I had a liberal arts college degree in my back pocket, and a notepad in my waitress apron. I wasn’t one to pray but I had done my own version: sending hopeful wishes out to the ether, which went something like “Get me out of here.”

I had graduated during an economic crash and felt stuck weighing tables. I wasn’t looking for a corporate job but had an inkling that I wanted to work in the arts. I had started curating some exhibits and was running a blog interviewing visual artists. So I took that full moon note as a sign, and dialed the number the mysterious man had jotted down.

It would have been easy to assume that this was the start of a romance, but my heart was miles away from that and I probably exuded unavailability. The first time I met with Gianluca, I mentioned my ex-girlfriend, making sure to clear the air of any potential spark. We ended up spending the evening looking through his photography work and discussing his creative process. He had moved from Italy to New York a few years prior and was increasingly shooting for magazines and a few fashion brands.

That initial conversation set the tone for our friendship, which crystallized around art, aesthetics, and creativity. It didn’t take long for Gianluca and I to become inseparable. We started meeting up almost everyday, spending hours walking the city and dreaming up various creative ideas.

Then, one day he called me. He had been working at a production company, shooting music videos and independent films. They were looking for a part-time assistant for him, so he asked me if I’d be interested.

My wish had finally been granted. I wasn’t completely out of the restaurant woods and still had to keep a few shifts, but I was starting to enter a new domain: the world of photography, film, and production.

I started assisting Gianluca and learned about camera lenses, lighting, and the production process. I became his second set of eyes and hands, filling in the gaps as needed, from coffee refills, to tracking SD cards, to easing the tensions on set. We mainly worked on small budget projects at the time, but they took us everywhere, from the Mojave Desert to Tuscany.

Set-life is an all-inclusive experience: you have breakfast, lunch and dinner together; sleep in the same hotel accommodations; and spend over 12 hours a day in a shared imaginary world.

When Gianluca and I were not on set, we continued inhabiting that all-encompassing lifestyle. Several times a week, we’d take yoga classes together at the community center. I’d prop up on his bicycle handlebars, as he’d navigate the bustling streets of the East Village. I was both terrified and thrilled –– any false movement would propel me face first into the pavement –– but I trusted Gianluca with my life.

We ate dinner together practically every night. Either we’d cook or I would bring leftovers from the restaurant. No matter how little we had – food, money, time– we’d pull our resources together. It never occurred to us to credit the giving or count the taking.

We’d spend our evenings discussing our projects; or exploring new creative endeavors. Gianluca was often picking up new instruments (flute, kalimba, handpan), while I enjoyed exploring new visual mediums.

It also wasn’t rare for us to share a bed, when the commute home was too long, or when one of us was between apartments. Never did we touch, beyond our platonic embrace.

Our respective circle of friends were often perplexed by our dynamics: how could we be so close, yet not “together”? To us, our friendship felt more like brotherhood and our shared blood was art.

When Gianluca was itching to leave New York, I knew our time was ticking. I didn’t try to hold him back. In fact, I longed to leave myself so I was envious of his trajectory. But I knew the distance would change the tides of our relationship. We’d continue to be friends and most likely collaborate, but our lives would no longer be merged as one. Our goodbyes lacked drama, but were infused with a quiet sadness, unspoken fears, and looming doubts.

We might have been too young to find the words to speak to each other. But I was reading

’s ‘Just Kids’ at the time, and came across a passage that perfectly summed it up, which I wrote in a letter to my friend:“‘What will happen to us’ I asked. ‘There will always be us,’ he answered.”

To listen to the audio interviews, play audio above.

For this final episode of The Friendship Series, I wanted to ask my friends about their experience of collaborating with friends. We discussed some of the rewards and challenges, and key ingredients for a successful creative friendship.

I interviewed friends from diverse creative backgrounds their experiences, including:

- : filmmaker

- : visual artist, writer, and educator

Michael Reynolds: filmmaker

Brandon D.: previously in a music band (now company founder)

Zandie Brockett: art curator

- : writer

- : musician and composer

Bianca Butti: filmmaker

For this week’s recommendations, I wanted to highlight 7 artistic friendships that have led to sensory creative collaborations: SEE, HEAR, SMELL, TASTE, TOUCH, BALANCE and ENVISION.

In Joy,

Sabrina

SEE

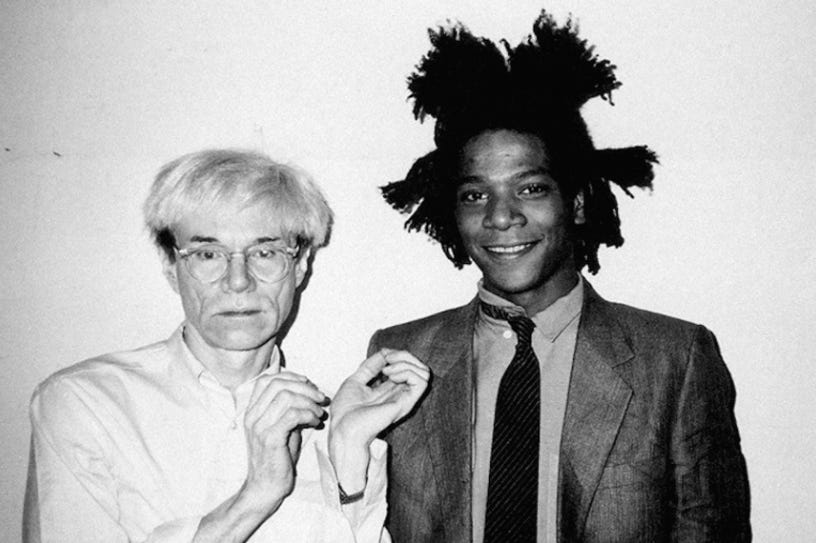

Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat

Read ‘Warhol on Basquiat’ book available online

One of the most legendary artistic friendships – Andy Warhol and Jean Michel Basquiat – was also the source of the most fruitful creative collaboration. During the six years the two artists collaborated, they created over 200 canvases together.

Warhol and Basquiat met briefly in 1979, when Basquiat spotted Andy Warhol at a fancy restaurant and sold him one of his postcards. Three years later, they were officially introduced via influential gallerist Bruno Bischofberger, who organized a lunch for the two artists. They immediately got along and just two hours after parting ways, Basquiat delivered “a painting to Warhol’s studio, Dos Cabezas, made after a self-portrait polaroid of the two at lunch.”

Warhol’s long-time assistant Ronny Cutrone’s describes their friendship: “It was like some crazy art-world marriage, and they were the odd couple. The relationship was symbiotic. Jean-Michel thought he needed Andy’s fame, and Andy thought he needed Jean-Michel’s new blood. Jean-Michel gave Andy a rebellious image again.”

Their first collaborative project was a mail art project, where Basquiat, Warhol and Italian artist Francesco di Clemente would “send each other’s partially finished canvases, in which one would add something to what he received from the other.” The collaborative paintings were shown in a show titled Collaborations, in Zurich in 1984.

The two artists started regularly collaborating and Baqsuiat would often paint from Warhol’s Factory. Their process entailed Warhol usually painting first, and then Basquiat adding his graffiti-style drawings on top.

As Keith Haring once put it: “Jean-Michel and Andy achieved a healthy balance. Jean respected Andy’s philosophy and was in awe of his accomplishments and mastery of color and images. Andy was amazed by the ease with which Jean composed and constructed his paintings and was constantly surprised by the never-ending flow of new ideas. Each one inspired the other to outdo the next. The collaborations were seemingly effortless. It was a physical conversation happening in paint instead of words…“

Their friendship seems to have been strained after their shared exhibit, Paintings, in 1985. Their work was met with heavy criticism by the media, and caused tension between the two artists. Sadly, their friendship didn’t recover as Warhol died suddenly in 1987 and Basquiat passed a year later.

HEAR

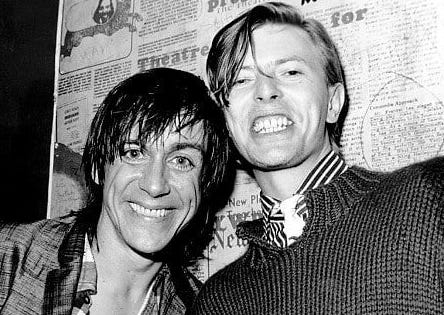

Iggy Pop and David Bowie

Listen to The Idiot and Lust for Life

There’s so many music bands that started or grew into friendships. And there’s just as many stories of dramatic band breakups. But beyond the stage, I was interested in a music collaboration that took place behind the scenes, and a life-changing friendship.

David Bowie met Iggy Pop in 1971 and convinced him to reform his band the Stooges. He co-produced their next album, 1973's Raw Power, which helped the band make a major comeback.

But Iggy Pop was descending into addiction and the band dissolved in 1974. A couple years later, Bowie and Pop reconnected and decided to go together to Berlin. Their hope was to wean themselves off their respective substance addictions and make music.

The plan turned out successfully. During their time in Berlin, Bowie and Pop focused on their work, aided by the sense of anonymity and freedom they felt. “Bowie would describe the setting in 1996 as a ‘haven of creativity.’”

Bowie would end up recording three albums, including Low, "Heroes" and Lodger. He also produced Iggy Pop’s first two solo albums, The Idiot and Lust for Life. They both played at each other’s performances: Bowie at the keyboard, and Pop singing vocals.

Iggy Pop describes their bond:

"He resurrected me. The friendship was basically that this guy salvaged me from certain professional and maybe personal annihilation — simple as that," Pop said. "A lot of people were curious about me, but only he was the one who had enough truly in common with me – and who actually really liked what I did and could get on board with it, and who also had decent enough intentions to help me out. He did a good thing."

SMELL

Gertrude Jekyll & Edwin Lutyens

Visit Munstead Wood

As a trained artist, Gertrude Jekyll had developed a wide mastery of painting, carving, carpentry, and embroidery. Once she started losing her eyesight, gardening took center stage in her life.

She was 45 years old when she met the 19 year old architect Edwin Lutyens at a tea party. An unlikely friendship was sparked between the well-connected Victorian craftswoman and the precocious and shy architect.

They started exploring local villages together and noting which buildings they liked. Jekyll “had strong views, but not the skill to realize them in three dimensions, so needed an architect and set about giving Lutyens an education in the Arts-and-Crafts style.”

The first dwelling Lutyens designed for Jekyll was modest by nature, as its name indicates ‘The Hut.’ They went on to collaborate on larger projects, such as the Munstead Wood, from where Jekyll’s famed nursery and garden design would materialize.

Jekyll’s network enabled the duo to earn large commissions, including the Lindisfarne Castle and the Deanery Garden in Berkshire for Country Life magazine founder Edward Hudson.

One of their quirkiest collaborations was a miniature castle and gardens created for the Queen’s Dolls House at Windsor Castle in 1924. The detailed construction, in collaboration with diverse craftsmen, included tiny formal walled garden with paved paths evergreen clipped hedges, potted plants and benches, even miniatures Rolls Royces.

Jekyll and Lutyens collaborated on over 100 gardens and designs, and Lutyens’ family referred to Jekyll as ‘Aunt Bumps.’ When Jekyll passed in 1932, Lutyens designed her gravestone at Busbridge church, Godalming.

TASTE

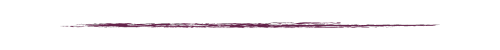

Julia Child & Simone Beck

Watch ‘Julia’ TV series (with Isabella Rosselini) | Available on Max, Hulu, Amazon Prime

+

Read Julia Child's memoir ‘My Life in France’ | Available at local bookstore and online

Julia Child met Simone Beck, nicknamed Simca, in 1951 at a party in Paris, They immediately connected, discussing "food, food preparation, food people, wine, and restaurants."

It wasn’t long before Child joined Simca as a co-teacher of her cooking school in Paris. The two spent the next 12 years writing and exhaustively testing recipes for their cookbook ‘Mastering The Art Of French Cooking.’

The cookbook finally came out in 1961 and Child started promoting it in the US. After a TV appearance on the show ‘I've Been Reading,’ where Child demonstrated how to make an omelet, the network was flooded with requests for more. Shortly, Childhad her own cooking show, ‘The French Chef.’

The popularity of Julia Child in the US was in stark contrast to the relative anonymity Simone Beck was experiencing in France. Since the cookbook was never translated into French, the spotlight was on Child.

Tensions between the two friends increased when publishers asked for a second volume of the ‘Mastering The Art Of French Cooking’ cookbook. Child wanted a larger share of the royalties, since it was her American audience that were driving sales. Beck reluctantly agreed, but the two never collaborated again.

Despite their collaborative turmoil, the two remained friends, continuing to vacation together in the South of France.

TOUCH

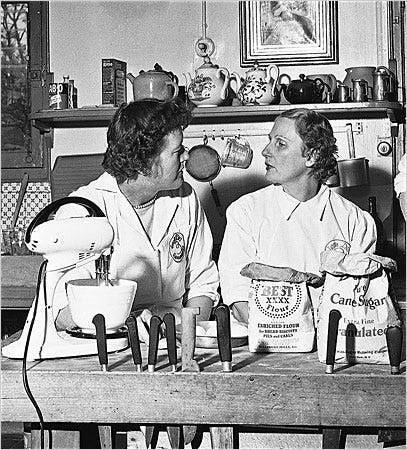

Yayoi Kusama and Donald Judd

Yayoi Kusama and Donald Judd met in the Fall of 1959. Kusama had her inaugural solo show at Brata Gallery in New York, and Judd wrote a review of it, as the recent art critic of ARTNews. He even bought one of the paintings (for $200).

Kusama’s paintings were a spark of inspiration for Judd who was just getting his start in Minimalism at the time. His son, Flavin Judd explains: “They helped him find a way through his work—and a direction out of representational painting. He started to make his flat plane paintings around the same time.”

The meeting left a lasting impression on Kusama as well. She wrote in her autobiography: “Donald Judd was my first close friend in the New York art world and he was the first to buy one of the pieces in the exhibition,” Kusama wrote in her autobiography.”

By the late 1960’s, Judd moved into the same building as Kusama, at 53 East 19th Street. He explained: “The fourth floor became vacant and [Kusama] told me about it. And so I got the loft and I lived there for 10 years or more because of her. So she was the neighbor downstairs.”

The two artists continued to influence each other’s work, both moving into sculpture around the same time. Judd even helped Kusama stuff her soft sculptures, including Accumulation no. 1.

Eventually, both artists moved out of the building and Kusama returned to he native Japan. But the two artists remained close and continued to correspond until Judd’s death. In a letter following one of Judd’s visits to Japan in 1978, Kusama writes: “Seeing you again here in Tokyo was just like a dream to me. [...] The thing [that] delighted me most was to see that you had become a truly mature and profound artist. (I hope I have matured as you have.).” Signing the letter: “Anxiously waiting to receive your artworks you promised to send me.”

When Judd was asked what he learned from Kusama, he responded: “A lot. She was a very serious artist. She really worked hard, but so did I. She was ahead of me in terms of developing her work and her paintings. She paid more attention or understood more thoroughly what had to be done about the paintings that Pollock, Newman, Rothko, and Still had done. To some extent, she was kind of a model for me.”

BALANCE

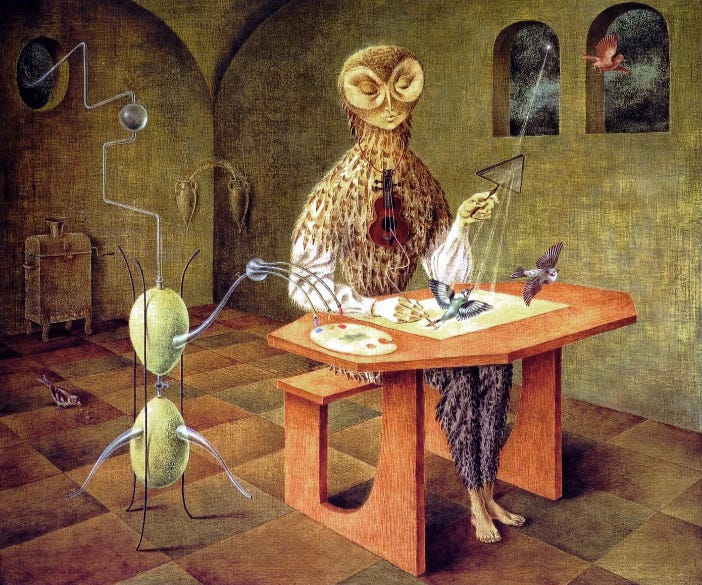

Leonara Carrington + Remedios Varo + Kati Horna

Book ‘Surreal Friends’ available (and pricey!) online

At the height of world war II, a number of artists fled Europe for safety. Amongst them were Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Kati Horna who all found a new home in Mexico City.

The three European women (respectively from England, Spain and Hungary) had all escaped persecution and shared an interest in alchemy, witchcraft, tarot and art. They formed a strong friendship and creative collaborations, and “created a surrogate family between themselves’.

Janet Kaplan, author of ‘Remedios Varo: Unexpected Journeys’ wrote of the group’s frequent “surrealist games, practical jokes, elaborate costume parties and raucous story-telling into the night.”

Domesticity and the theme of home were central parts of their work. Carrington’s biographer, Susan Aberth wrote: “One of [Carrington’s] primary means of reclamation [of feminine agency]… was to equate the feminine domestic sphere with magical practices of diverse cultures. Thus the nursery, the kitchen, the kitchen garden, and so on, were transformed from sites of feminine drudgery and oppression into sites of contestation and power.”

Carrington and Varo enjoying concocting magic potions from the herbs they’d gather at the Mexican markets and cooking surrealist meals. They turned their daily life into a magical act, which also permeated their work, as seen in paintings such as ‘Friday’ or ‘Night of the Eight’(Carrington), and Varo’s ‘The Creation of the Birds.’

The artists believed not only in equality between the sexes, but were also curious to explore the female magic power from ancient pagan religion and traditions. As Carrington wrote:

“Most of us, I hope, are now aware that women should not have to demand Rights. The Rights were there from the beginning; they must be Taken Back Again, including the Mysteries which were ours and which were violated, stolen or destroyed.”

ENVISION

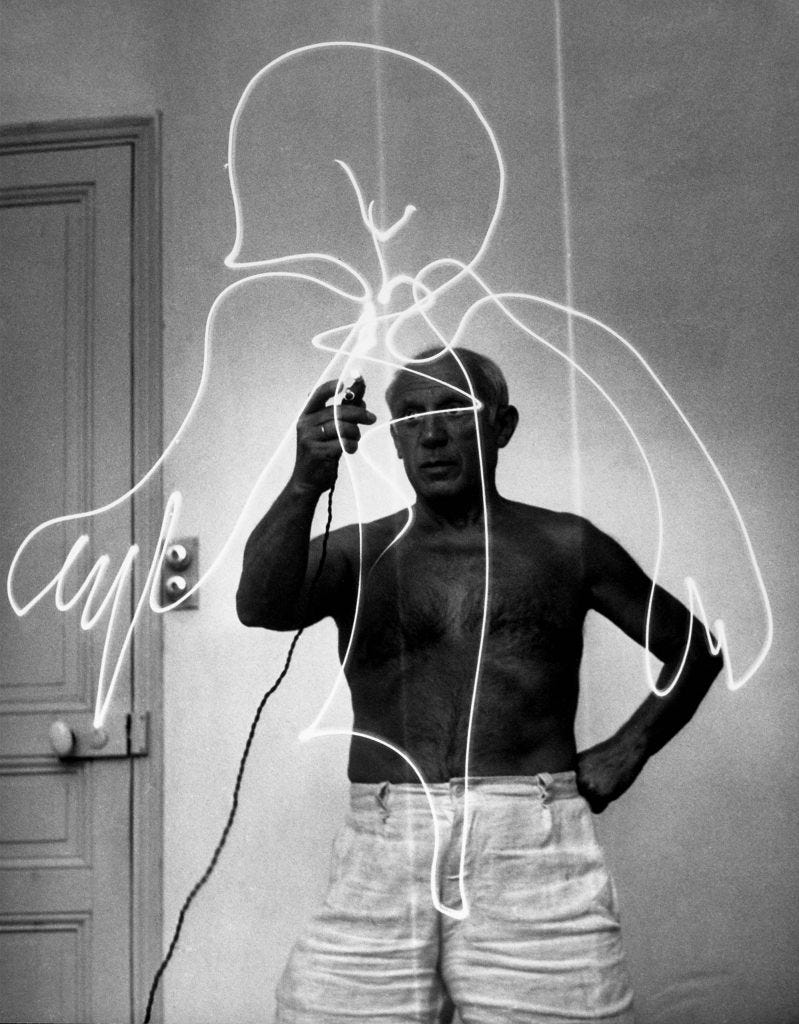

Pablo Picasso and Gjon Mili

In 1949, LIFE magazine photographer Gjon Mill was sent to take portraits of Pablo Picasso in his French home in Valluris.

Mili wanted to try a photo experiment, and Picasso granted him 15 minutes to do so. The photographer set up two cameras in a darkened room, one for front view and the other for side. He left the shutters open and prompted Picasso to draw in the air with a small electric light.

Picasso was so fascinated by the process that he agreed to collaborate on five additional photography sessions, creating over thirty iconic images. During the photoshoots, Picasso would draw centaurs, bulls, Greek profiles and his signature – all from light in air.

The “light drawings” as they famously became referred to, were essentially invisible. But the camera could capture Picasso’s process, turning the ephemeral artwork into legendary images. In 1950, the Mili/Picasso photography series was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Fantastic post, Sabrina, I’ve always been fascinated by the life of Kusama and also her relationships with Judd and Cornell. Thank you!

One of my favorite Seven Senses! I loved hearing details of how your friendship w Gianluca started and developed. And the friend collaborations suggestions were wonderful. I’d never connected the dots w many of these artists. Now onto the audio interviews!