What happened to hobbies?

I remember seeing that tweet a few years ago (pre-pandemic), and it stopped me in my tracks. The internet stranger had a point. At that time, it had been years since I had really engaged in a true hobby. Most of my time was spent on my work, or activities that would engender more work. Even seemingly leisurely time – such as grabbing a drink with someone, attending music festivals, or visiting art fairs – were still under a professional premise.

Working in creative fields, I didn’t think I needed a hobby. After all, as a multi-passionate – or a ‘multi-hyphenate’ as

calls it – I strived to turn my various creative interests into a career. As a result, my resume is a patchwork: writer, art curator, magazine editor, photographer’s agent, record label executive, etc – loosely sewn with a creative thread.But my passions didn’t always fit within the limited confines of a job description. When my interests weren’t easily marketable they were often abandoned, rather than pursued as hobbies. Some of it was motivated – or restrained – by the financial pressures of living in expensive cities like New York and Los Angeles. I felt the need to be strategic about how I spent my time, and whether that activity was conducive to my career’s growth. It doesn’t help that capitalistic systems encourage us to turn any hobby into a profitable business. So engaging in activities that don’t directly feed our livelihood can seem like a waste of time (and money).

But pursuing hobbies isn’t just a luxury for those who have free time: it’s an exercise in getting to know ourselves. In the exploration, we discover new pleasures, hidden talents, and dormant dreams waiting to be awakened.

Sounds enchanting – but it’s also frightening. What if we don’t like what we discover about ourselves? What if we’re not good at it? What if it doesn’t neatly fit within the image we’ve constructed?

I recently discovered that Victor Hugo, known for his novels ‘Les Miserables’ and ‘The Hunchback of Notre Dame,’ was also an avid painter. He created over 4,000 drawings during his lifetime, but only shared his artwork privately – as he was afraid they might overshadow his literary achievements.

The fear of judgment, rejection, humiliation, often refrains us from exploring, or sharing, our various interests. I often hold back in revealing my ‘spiritual’ side. Even writing about astrology recently felt risky, though it’s a practice that’s increasingly become accepted in mainstream culture. The fear is that my interests in mysticism and esoteric studies will come across as too woo-woo – conflicting with the more rational, serious, and practical image I wish to convey (or that others expect of me).

I admire those who have the courage to integrate their disparate passions into their lives – even when they seem in opposition. I was fascinated to recently meet a Christian missionary who worked as a marine biologist. He had lived around the world, devoting his life to both science and religion. I was stunned, and asked him: “So who is more judgmental (of his incorporated duality): your scientific peers or your religious community?” He smiled and answered: “Both, equally.”

“We contain multitudes” is one of my favorite lines by Walt Whitman (Section 51 of ‘Song of Myself). But the two lines that precede that statement are just as important:

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

Not only do we contain multitudes, but we’re made of contradictions. We strive to “make sense” – to be a cohesive and logical unit, rather than accept and discover the many layers we hold. We can be scientific and religious; intuitive and rational; material and spiritual.

Rather than fear our inner contradictions, we can start exploring them – following our sparks of interest, pulling on the thread of curiosity – and see where it takes us. Whether it makes sense or not, let the crumbs of inspiration lead a path to wonder.

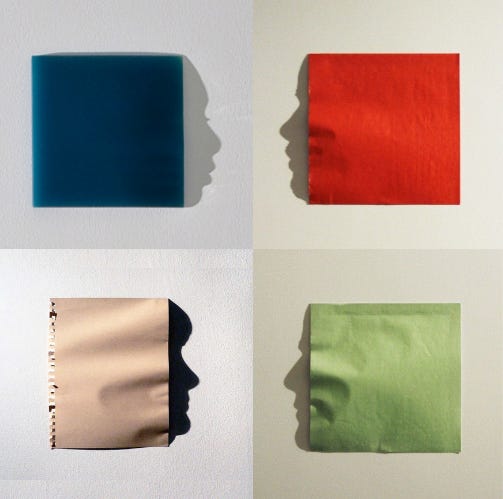

Instead of my typical recommendations this month, I’m highlighting 7 artists and their sensory hobbies. I hope they inspire you to explore your own passions through your senses – See, Hear, Smell, Taste, Touch, Balance, and Envision.

In Joy,

Sabrina

PS: I learned about many of the examples below when reading the book ‘Birds, Art, Life’ by Kyo Maclear (which I discovered via my new Substack friend

). For more details on spotlighted artists, I’ve also linked to some posts by two of my favorite Substacks: by and by .SEE

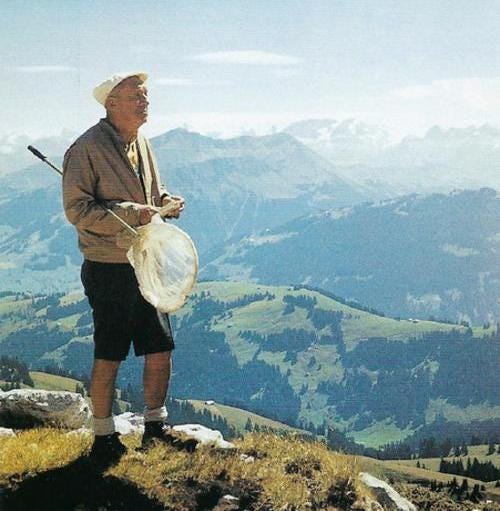

Vladimir Nabokov & Butterflies

When Vladimir Nabokov wasn’t writing, he was out chasing butterflies. A true enthusiast of lepidopterology (the science of butterflies), “he was responsible for organizing the butterfly collection of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University” in the 1940s.

His interest started when he was a young child, and proposed a Latin name for a subspecies of poplar admiral that he had spotted near his family’s estate. It turned out that it had already been identified a few years prior. But as an adult, he succeeded in discovering and naming multiple species, most famously the Karner blue (Lycaeides melissa samuelis), which he came across in upstate New York, in 1944.

In a Paris Review interview in 1967, Nabokov commented:

“The pleasures and rewards of literary inspiration are nothing beside the rapture of discovering a new organ under the microscope or an undescribed species on a mountainside in Iran or Peru. It is not improbable that, had there been no revolution in Russia, I would have devoted myself entirely to lepidopterology and never written any novels at all.”

For more details, I recommend reading this Art Dogs post.

HEAR

Haruki Murakami & Jazz

Before Murakami started writing, he used to run a jazz bar and coffeehouse in Tokyo, named Peter Cat. He named it after his cat, which you can read more about in this beautiful profile by

. Murakami and his wife were both jazz lovers and juggled multiple part-time jobs so they could finally open Peter Cat, their coffee shop and jazz bar in 1974. Peter Cat was a culmination of everything Murakami loved, but running the establishment was a challenge.The operation proved to have a fruitful creative effect on Murakami though. Shortly after opening, he started writing. Music and writing became inextricably linked:

“It may sound paradoxical to say so, but if I had not been so obsessed with music, I might not have become a novelist. Even now, almost 30 years later, I continue to learn a great deal about writing from good music. My style is as deeply influenced by Charlie Parker’s repeated freewheeling riffs, say, as by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s elegantly flowing prose. And I still take the quality of continual self-renewal in Miles Davis’s music as a literary model.”

Even his book titles are inspired by songs: 'Norwegian Wood' comes from The Beatles song; ‘Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage’ was inspired by ‘Années de pèlerinage’ a solo piano set by Liszt; and the story “A Slow Boat to China” was named after a 1948 Frank Loesser song.

SMELL

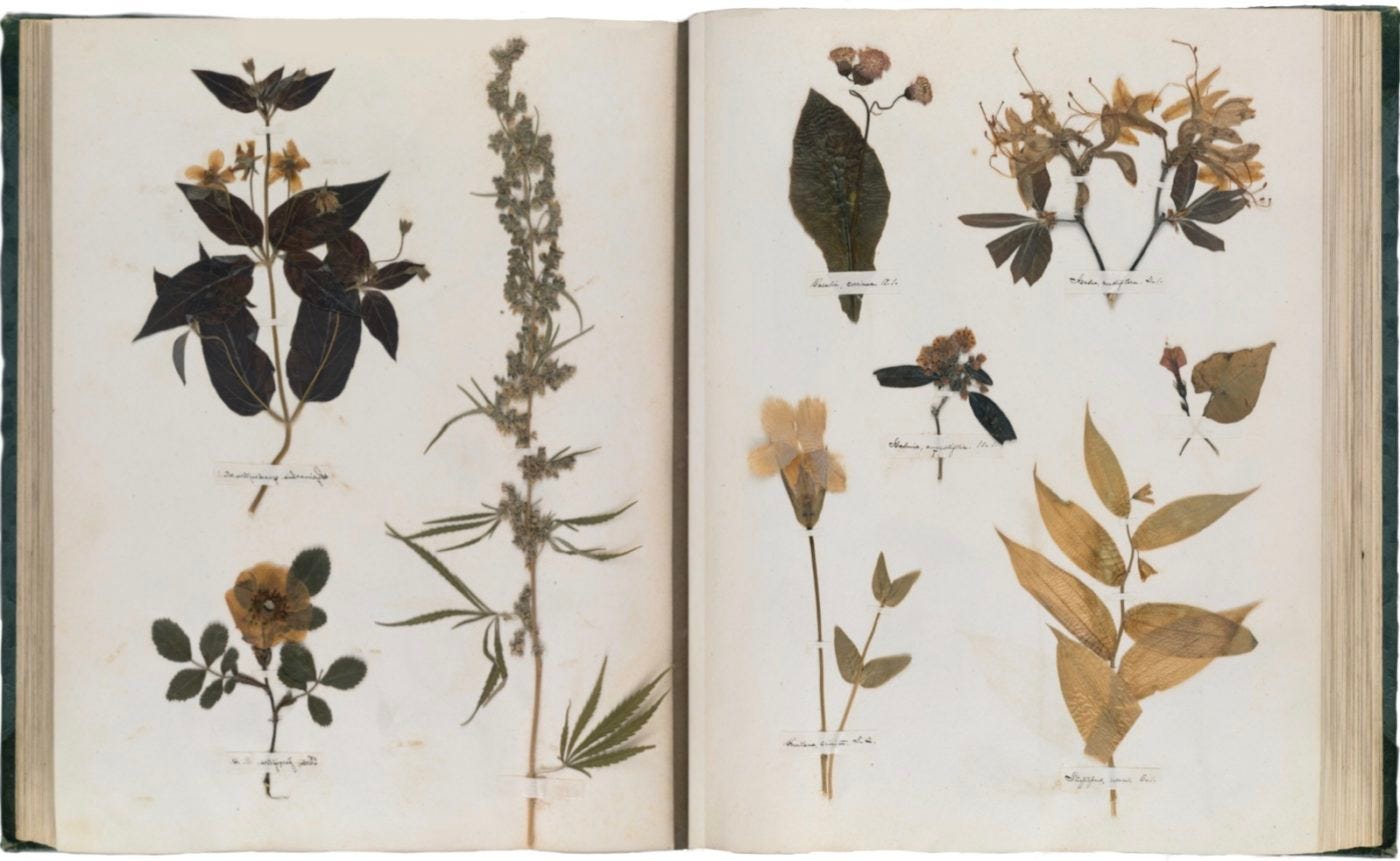

Emily Dickinson: Baking & Botany

“I am going to learn to make bread tomorrow. So you may imagine me with my sleeves rolled up, mixing flour, milk, saleratus, etc., with a great deal of grace. I advise you if you don’t know how to make the staff of life, to learn with dispatch.”

– Emily Dickinson to Abiah Root, September 25, 1845

Emily Dickinson became so skilled at baking that her father approved of no other bread except hers. Her Indian and Rye bread even won second prize in the Amherst Cattle Show of 1856 (although her sister Lavinia was one of the judges).

She often found inspiration while baking, and would write lines of poetry on the backs of recipes and food wrappers. She started a poem (“The things that never can come back, are several –”) on the back of her coconut cake recipe, which is still in circulation today.

According to the Emily Dickinson Museum, the kitchen “was a space of creative ferment for her, and that the writing of poetry mixed in her life with the making of delicate treats.”

Baking wasn’t her only hobby. She was also a passionate botanist from a young age. As a fourteen-year-old, Emily Dickinson “assembled an herbarium of over four hundred specimens collected in the fields and woods around the family home in Amherst, Massachusetts” in a leather bound album, which is now held and digitized by Harvard’s Houghton Library.

From the 1,800 poems discovered after her death in 1886, “more than a third draw on her vast horticulture knowledge and imagery from her garden and the surrounding land.” To dive into Dickinson’s botany drawings and other notebooks, I highly recommend this ‘Noted’ post.

TASTE

John Cage & Mushrooms

“I have come to the conclusion that much can be learned about music by devoting oneself to the mushroom.” – John Cage

The quote is from a two-volume study of the American composer’s mycology passion. It includes texts and reproductions of Cage’s mushroom poetry and his 1972 Mushroom Book.

Cage’s mushroom obsession started during the Great Depression, when he began foraging out of necessity. He later recalled: “I didn’t have anything to eat, and I knew that mushrooms were edible and that some of them are deadly. So I picked one of the mushrooms and went in the public library and satisfied myself that it was not deadly, that it was edible. And I ate it and nothing else for a week.”

His passion grew from there, and his knowledge expanded. In the late 50’s he won five million lire on an Italian TV quiz show about mushrooms. Surprisingly, Cage wasn’t interested in the psychoactive effect of mushrooms – he never took drugs in his life, he said.

What he was more interested in was the act of foraging. The passion came with its own risks, which Cage wasn’t immune to. In 1954, he almost died after ingesting a poisonous mushroom – confusing hellebore for skunk cabbage. But his brush with death didn’t deter his mushroom fascination.

Despite his growing success as a music composer, Cage still struggled financially and mushrooms became a way to supplement his income – he started supplying them to renowned New York restaurants.

He also taught a mushroom identification class at the New School in New York, with botanist Guy Nearing. On weekends, they’d take their students mushroom foraging in upstate New York. They also helped re-establish the New York Mycological Society, which continues to this day.

Cage wasn’t interested “in the relationships between sounds and mushrooms any more than I am in those between sounds and other sounds.” But the act of foraging created a space for his compositions to take shape. Once, when he was asked why he composed music, Cage responded:

“I do not deal in purposes; I deal with sounds. I make them just as well by sitting quite still looking for mushrooms.”

TOUCH

Sylvia Plath & Bees

A love for bees runs in Sylvia Plath’s family. Her father Otto was “an entomologist who specialized in bees, and his book ‘Bumblebees and Their Ways’ (1934) is still highly regarded today.”

But it wasn’t until late in her life – the year before she died by suicide – that Sylvia picked up the hobby. She immediately took to it, writing to her mother:

“Today, guess what, we became beekeepers! We went to the local meeting last week…We all wore masks and it was thrilling…Mr. Pollard let us have an old hive for nothing which we painted white and green, and today he brought over the swarm of docile Italian hybrid bees we ordered and installed them…I feel very ignorant, but shall try to read up and learn all I can.”

Plath enjoyed the hands-on approach to beekeeping – a refreshing contrast to writing. She was attracted to those who had practical skills, who could tend to the natural world:

“I must say what I admire most is the person who masters an area of practical experience, and can teach me something. I mean, my local midwife has taught me how to keep bees. [...] As a poet, one lives a bit on air. I always like someone who can teach me something practical.”

Some of her last poems revolved around bees, including ‘The Bee Meeting,’ ‘The Arrival of the Bee Box,’ as well as ‘Stings’ and "Wintering."

BALANCE

Writers and Swimming

Swimming and writing seem like a symbiotic marriage. I couldn’t pick a single author to feature, since a multitude of writers seem to be attracted by the buoyancy of water.

I first noticed the connection between writing and swimming, when learning about the relationship of writers and alcohol in Olivia Laing’s book ‘A Trip to Echo Springs.’ Beyond alcoholism, the stories also revealed that many of the profiled authors – F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, John Berryman, John Cheever and Raymond Carver – were also avid swimmers.

In Cheever’s short story ‘The Swimmer,’ he writes: “To be embraced and sustained by the light green water was less a pleasure, it seemed, than the resumption of a natural condition.”

Swimming is both an escape from words, and a way to conjure them into our consciousness. The muses can flow in water and transport us along a creative stream. As Fitzgerald famously said: “All good writing is like swimming underwater and holding your breath.”

ENVISION

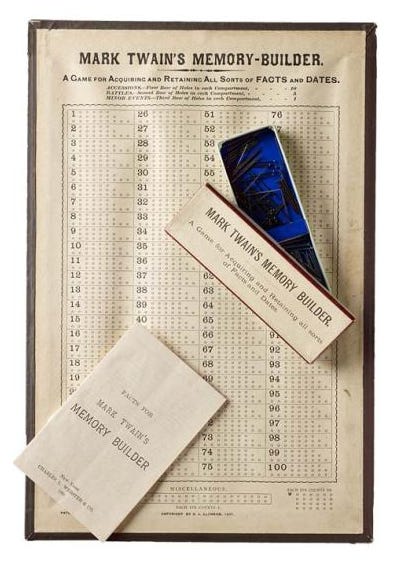

Mark Twain and Inventions

Beyond being a prolific writer, Mark Twain was also an avid inventor. In today’s world, we’d call him an entrepreneur. His first foray was investing in a typesetting machine in 1889 – which led to bankruptcy. He also started a publishing house, which was surprisingly also unsuccessful. But he wasn’t deterred and, encouraged by his friends Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla, he patented 3 inventions:

The Self-Adhesive Scrapbook which went on to sell over 25,000 copies (more details in this post by

)His “Memory-Builder”, which was a history trivia game aimed to help children study important historical dates.

The "Improvement in Adjustable and Detachable Straps for Garments." Originally, Twain envisioned it as a replacement for suspenders, but the item never really caught on in that market. Instead, the strap became standard for bras, and still used today.

This is such a gorgeous letter thank you Sabrina. I also had a similar revelation recently when I recently discovered I didn’t really have hobbies but instead had short-lived intensely passionate bouts of finding something new I’m interested in—knife sharpening, woodworking, miso, the science behind scent / perfume etc etc. I find it keeps life interesting and keeps me on my toes! I often wonder what I will I become fascinated with next!

“What did you do as a child that made the hours pass like minutes?” I read a while back on Substack. It’s rare that, as adults, we indulge in play or a hobby. We are living in this hyper-productivity-obsessed society where we are being told that everything we do needs to turn into a business or needs to have some purpose. But I do think this doesn't seem right. Not everything we do in life must be about being productive or generating income. Resting, daydreaming, and playing are as important as eating and sleeping for a balanced and healthy life. We underestimate the importance of these things. These are also critical things for our creativity. My best ideas sometimes came from doing nothing or pursuing a hobby, just having fun. These days, we need to make a conscious effort to make time for play and hobbies, as everything around us tells us otherwise. It’s easy to get blinded and run on autopilot without taking time for a hobby. Thank you for this great post, Sabrina