Nature’s clock has turned to Spring. The white blanket of winter is melting, revealing new fertile ground. It’s the season of hope, a time of renewal. There’s movement, desire, possibility in the air – the excitement of a meal, a mate, or a new adventure.

I marvel at nature's rhythm, its internal knowing, its delicate harmony. And I remind myself, I’m not just an observer – I’m part of it too.

The illusion of separateness with nature and a desire to dominate over it has prevailed Western thought. And we’re all experiencing the toll of it. Yet we still struggle to embody the fact that we are Nature; how we (mis)treat it is a reflection of ourselves.

I was reminded of this a few years ago by Pancho, a pilgrim whom I was lucky to welcome in our home for a night. He was walking from Northern California to Mexico, carrying a flag of the Earth. He told me about the many agriculture fields he passed along the way: perfectly aligned rows of monocultures, heavily sprayed with pesticides, depleting a soil hungry for diversity. Pancho believed the fields were like our minds – a representation of our rigidity, our greed, our propensity to order, separate, and control.

But that’s not how Nature works. It does not come arranged in perfect rows of sameness. It is curvy and unruly, expansive and wild. Nature thrives on diversity and creates from chaos.

We’ve constructed an imaginary ladder of superiority – even named it a kingdom – and placed ourselves on top. But the more we discover about the communication of trees, the empathy of ants, and the memory of crows, the less special we become.

It takes humility to step down our illusory throne, and be part of the whole. To give up dominating, and instead turn to cooperating. Yet our own survival and thriving depends on it. As we seek to rebalance the state of our planet, we can turn to Nature for guidance.

Every mineral, plant and animal has something to teach us. Nature’s law is based on creativity, sufficiency, and reciprocity – principles we can apply to our own lives.

This month’s Seven Senses is an invitation to experience Nature through our senses – see, hear, smell, taste, touch, balance and envision.

In Joy,

Sabrina

SEE

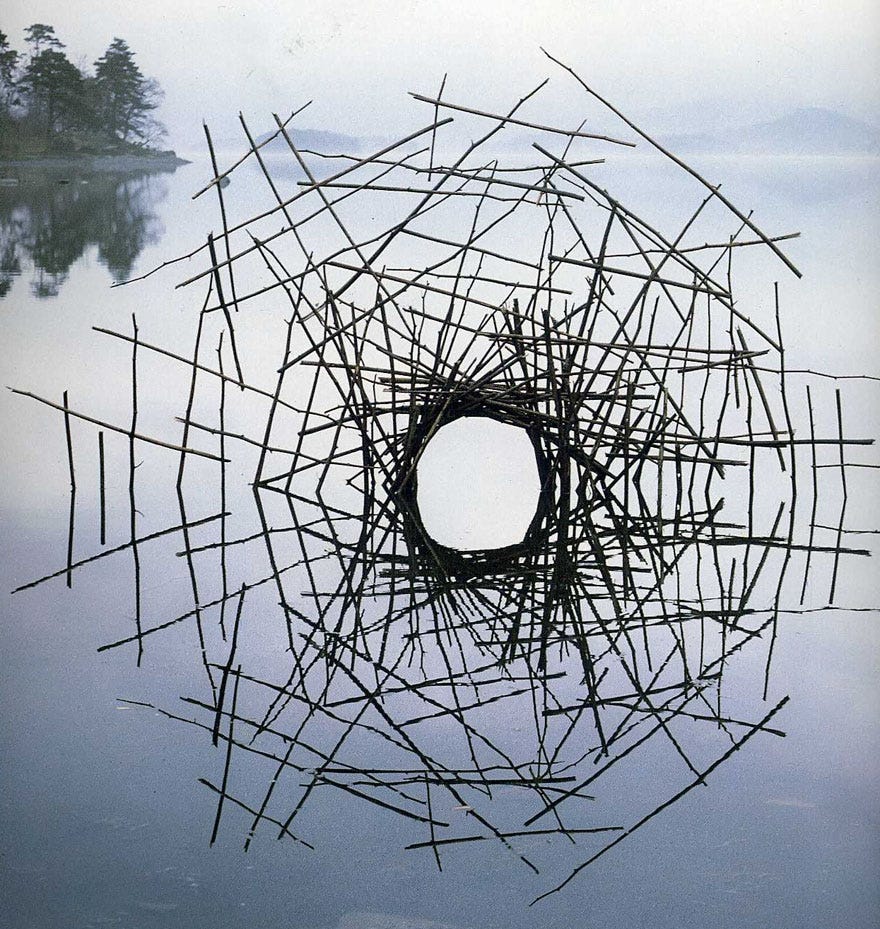

Andy Goldsworthy | art + documentaries

“Rivers & Tides” (2002) and “Leaning Into the Wind” (2017)

Working in harmony with Nature is at the heart of Andy Goldsworthy’s art. Known for his outdoors installations, he solely uses elements found in nature: leaves, soil, rocks, ice, etc. It takes Goldsworthy many hours and failed attempts to construct an elaborate sculpture. Once the work is completed, he documents it, and then watches it disintegrate – melted by the sun, carried out by the ocean, or blown away by the wind. He leaves no trace, only a memory captured on photograph.

Though most of his art is ephemeral, some of Goldsworthy’s work is exhibited in museums and parks internationally. I was lucky to see one of his sculptures, in Presidio Park, on my last visit to San Francisco. I also often reference his books, a few of which live in our home including “Time” and “A Collaboration with Nature.”

One of the best ways to experience Goldsworthy’s artwork though is by witnessing his process. Two documentaries, by filmmaker Thomas Riedelsheimer, meticulously portray the artist at work: “Rivers & Tides” (2002) and “Leaning Into the Wind” (2017).

HEAR

Nature Harmony | music playlist

Spotify Playlist curated by

I was delighted to discover

, thanks to my friend who writes .Everyday, Flow State curates two hours of instrumental music, highlighting one artist with a bit of their background. Flow State’s repertoire is fascinatingly eclectic – ranging from Swedish ambient music to psychedelic Thai bands and Turkish singer-songwriters.

For this month’s Seven Senses, Flow State curated a dreamy ‘Nature Harmony’ playlist. Here’s a description they provided to enhance your listening:

Human beings are not apart from nature; we are nature. This playlist collects music that acknowledges and expresses this.

Japanese "environmental music" in the '80s taught people that artificial music from synthesizers could in fact reconnect us with the earth. More recent music from GAS, Nils Frahm, and Trent Reznor has channeled gaia, offering those of us living in artificial environments to reinhabit primordial headspaces.

In other words, headphones plus ambient music equals a mindset we used to hold but have, with recent "progress", forgotten.

Enjoy 'Nature Harmony' on Spotify. Thank you

for this beautiful contribution.SMELL

Forest Awakening | mud and dew, wind and warmth

Observation by , writer of

We often use visual cues to assess the health of Nature – the sights of dwindling coral reefs have given us sharp insight into the state of our planet. Conversely, we’ve also seen what regeneration can look like, with the reintroduction of wolves in YellowStone, as one example.

But beyond sight, I was curious to learn if we can also smell nature’s harmony?

I turned to field biologist, and fellow Substack writer

for some guidance. I was glad to catch Bryan prior to his expedition into the Everglades. He was able to report from the grounds, with his lived experience of the scent of Spring:The promise of Spring is the breathing of dirt. In the naked woods of home, before the eruption of wildflowers and warblers, before the carnal meets the vernal, soil sends forth the aromas of a new season.

Here in Vermont, where we enjoy more than four seasons, it is mud season. Our dirt roads, rutted and soft, can seize your truck to its axels. But in the woods it is a season of mud giving, of leaf litter nourishing, of trees pledging — a forest releasing all that it held in trust through winter.

There is no revelatory smell to this release. Not like the sweet signature of honeysuckle or the aromatic summons of balsam poplar. They will come later. Now instead we inhale a vague fusion of mud and dew, of wind and warmth.

Maybe it’s simply that there now exists any smell at all in these woods — new to our nostrils after a winter of crisp, vacant air. So I sit on a fallen ash, close my eyes, breathe with the forest, try to parse its scents.

And yet I recognize that the smell of this place is greater than the sum of its fragrances. Greater than me. It is the aroma of harmony, of a forest community, an expression of a new season.

It is the sense that not only do I belong in these breathing woods — but that I belong to these breathing woods.

Thank you

. I appreciate your patience and perseverance - a true Spring lesson – in sharing your insightful observations. Learn more about Bryan’s work .TASTE

The Three Sisters | Indigenous agriculture

Here’s a taste of patience: growing your own food. As

of beautifully states:“Gardening is a contract with hope… an exercise in promise and potential.”

Even though I currently live in a Los Angeles apartment, I dream of someday moving to the countryside and planting a vegetable garden. When that time comes, I’d like to do it without the use of chemicals. Any gardener will tell you that pests are unavoidable. But when nature challenges us, it also offers us solutions. And often, the key to harmony is collaboration.

I first learned about the ‘Three Sisters’ in Robin Kimmerer’s exquisite book “Braiding Sweetgrass.” This indigenous agriculture method involves planting seeds of corn, beans and squash together. Kimmerer explains:

“For millennia, from Mexico to Montana, women have mounded up the earth and laid these three seeds in the ground, all in the same square foot of soil. When the colonists on the Massachusetts shore first saw indigenous gardens, they inferred that the savages did not know how to farm. To their minds, a garden meant straight rows of single species, not a three-dimensional sprawl of abundance.”

Yet there’s a reason for this “sprawl of abundance.” Each plant grows at a different pace, and helps each other along the way.

First comes the corn, which builds a strong stem. Then the beans, which initially grow close to the ground and then start climbing up the corn stalk. Kimmerer explains: “Had the corn not started early, the bean vine would strangle it, but if the timing is right, the corn can easily carry the bean.”

Then comes the pumpkin or squash, the “slow sister.” Their bristly leaves extend over the ground, protecting the corn and bean by keeping the moisture in and repelling caterpillars and other plants.

As Kimmerer reminds us:

“The beauty of the partnership is that each plant does what it does in order to increase its own growth. But as it happens, when the individuals flourish, so does the whole … Together their stems inscribe what looks to me like a blueprint for the world, a map of balance and harmony.”

Growing the Three Sisters:

In the Spring:

- Prepare the soil by adding wood ash or compost to increase fertility.

- Make a mound of soil about 1 foot high and 4 feet wide.

- When the danger of frost has passed, plant the corn in the mound. Sow six kernels of corn 1 inch deep and about 10 inches apart in a circle that is 2 feet in diameter.

- When the corn is about 5 inches tall, plant 4 bean seeds, evenly spaced, around each stalk.

- A week later, plant 6 squash seeds, evenly spaced, around the mound.

TOUCH

Natural pigments | painting

I featured some of my beet paintings in “Got a Moon Room?” and I was curious to further explore with natural pigments.

Creating from Nature is an ancient practice. The earliest recorded applications of natural pigments dates 5,000 BC at the “Cave of Hands” in Argentina. In Ancient Egypt, new techniques to fix natural dyes and mine new colors were developed.

Pigments were often mixed with egg and water to create a dried protein that would bind the pigment to the substrate. Walnut or linseed oil, which dried slower and created a more versatile paint, was then introduced in the 15th century.

Pigments were often referred to by the location in which they were produced. For example, Raw Sienna and Burnt Sienna came from Siena, Italy, Egyptian Blue from Egypt, French ultramarine from France, and so on.

Natural dyes can be obtained either from plants, animals or minerals. I had intended to try out minerals by collecting rocks on a hike. But the Los Angeles rain prevented that mission, so I turned to my kitchen for some plant materials

I also experimented with the PH balance to see how the pigments would react. Red flowers and foods tend to be naturally more acidic, while blue and purple tend to be more alkaline. Adding lemon or vinegar (acidity) and baking soda (alkaline), can alter these colors.

For each ingredient, I made three versions: one neutral, one with vinegar, and one with baking soda. I didn’t use any binders, such as arabic gum and honey or glycerine, which are typically added to preserve the color. Here are a few of my observations for each of my seven pigments:

Spirulina: initially the vinegar and baking soda did not make a difference. But the next day, the acidic version was brighter and the alkaline was a darker hue.

Cabbage: this was my favorite to experiment with as it offered the most range of colors. Interestingly, the vinegar version originally was fuchsia and then turned turquoise. Later, I added more vinegar to it, and this time the color stayed pink.

Rose petals: when I added vinegar to the mixture, it turned bright pink but then dried out into a light beige and then pale green. The baking soda version first turned it green and eventually into a straw-yellow.

Sumac: this spice is typically a deep aubergine color but when diluted it appears more brown. This was the only ingredient that had a noticeable chemical reaction when I added baking soda: the mixture became very bubbly. So perhaps best to avoid. The vinegar mainly diluted the color and the baking soda turned it a dark brown.

Cinnamon: I used a very fine sieve for all the spices but both the sumac and cinnamon remained grainy. You can wipe it off when it dries but I kept it for texture. No noticeable change with acidic nor alkaline variations.

Paprika: the paprika turned smoother than sumac or cinnamon. The deep ochre color reminded me of some mineral paints, made from rocks and red soil.

Turmeric: commonly used as a natural yellow coloring. It’s vibrant and takes hold easily. The vinegar barely made a difference, but the baking soda had a stronger effect, turning it a deep red.

BALANCE

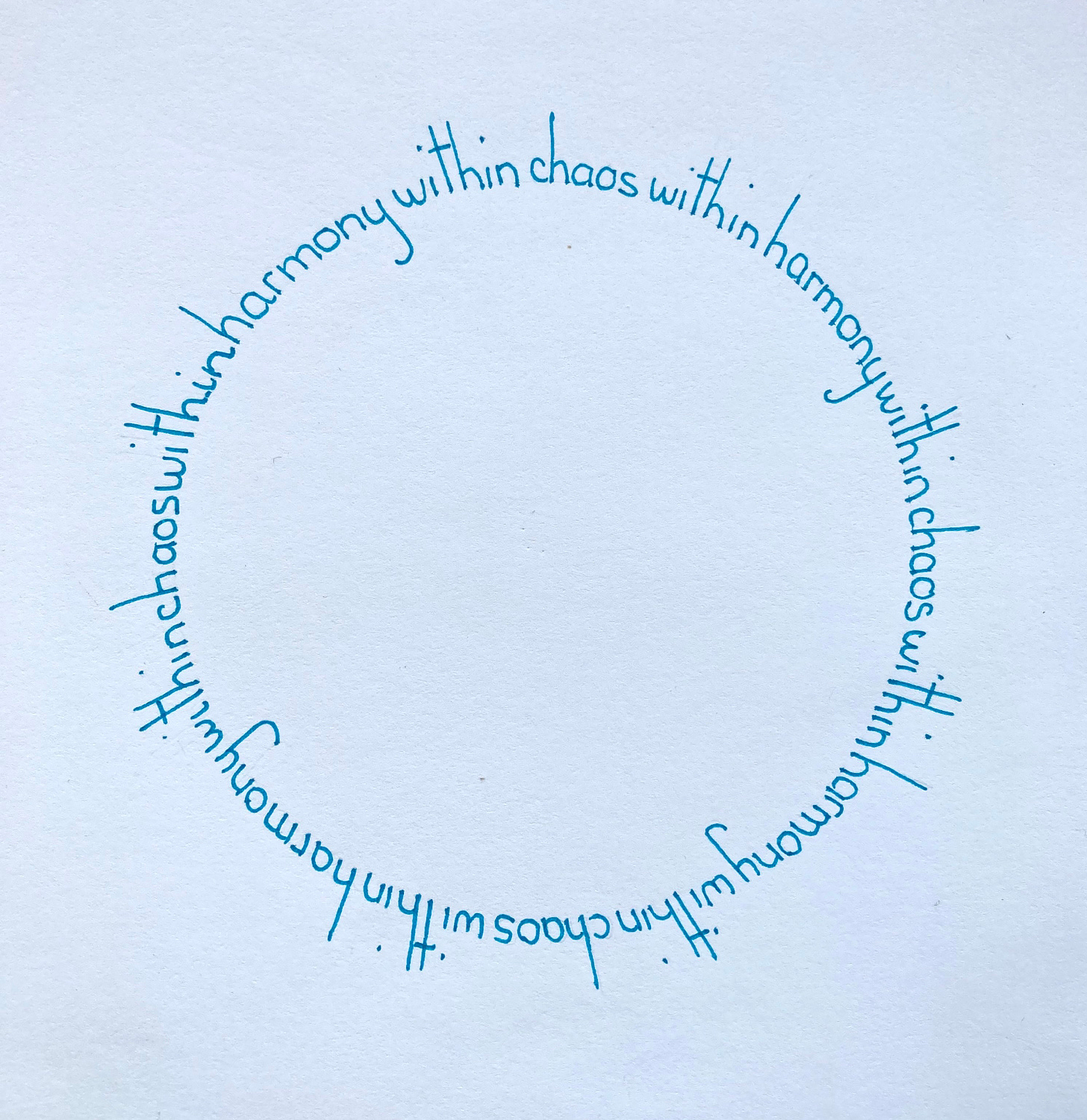

Circle Mantra | visual meditation by Kenshō studio

This month I’m offering something a bit different from my Jumbled Mantras. Nature has its cycles, and this mantra follows that circular form. Turning to Nature for balance, I receive the following message:

Harmony within Chaos…

Sit with these words, let them swirl within you. By observing our bodies, our minds – our own nature – we can experience chaos and harmony within ourselves. The two are intertwined. As Alan Watts once said: “Discord on one level is harmony on another.”

ENVISION

Redwood Wisdom | video poem by Kenshō studio

One of my favorite places on Earth are the Redwoods of California.

The tallest trees on Earth, Redwoods can reach up to 350 feet (100 meters). They’re also some of our most ancient trees. They’ve been around for 240 million years. The oldest living Redwood we know of is 2,200 years but foresters believe some coast redwoods may be much older.

Redwoods create a balanced ecosystem for the whole forest. Their leaves can both absorb moisture from fog and also condense it back into rain, helping the forest keep cool and moist during dry months. They filter the air, storing more carbon than any other tree on Earth.

Since Redwoods are resistant to rot and fire, it’s made them particularly appealing to lumber and as a result only 5% remain.

I didn’t know any of these facts when I first experienced the California Redwoods. But you can feel that majestic power in their presence. Their incredible height, their color, the way they tightly grow together, makes me feel protected, rooted, at peace.

This poem was written while spending time with these wise elders.

Share this post