On March 6th, I celebrated 36 years on this planet, in this body.

The next day, my father left this Earth, out of his body.

For a night, life and death overlap.

Call it cruel irony, call it divine timing.

Grief is the most universal human experience. Yet it is so deeply personal.

We all grieve in our own way, and grief takes new form with each loss. Grief also morphs over time, so I can only speak from where I stand today.

This is not my first encounter with grief, but it is my initiation in losing a parent. As a dear friend recently told me: “There’s a before, and an after – you’re never the same after the death of a parent.”

And I’m starting to understand what she means. I’ve been catching glimpses of the transformation. But I’m not fully in the “after” yet, I’m still oscillating the–in–between. If grief is an ocean to traverse, I’ve just set the sails. I hear it’s a long and choppy journey ahead, but I didn’t suspect it could also offer a new sense of freedom.

I used to associate grief with sadness, tinged perhaps with regret. I was acquainted with the “five stages of grief” which are defined as denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. But my experience so far has been more nuanced and complex.

If my first stage of grief had a name, it would be “discombobulated.” Those first few nights were restless, tossing and turning in bed. During the day, I sleep-walked in a forgetful state – losing items of clothing, driving past my house on my way home, and leaving groceries behind. It’s as if my body and mind were disconnected, having lost their bearings.

Emotions aren’t felt as neatly as the labels we ascribe to them and what followed has been a blend of anger, sadness and relief. Losing a loved one means letting go of any expectations we had of that relationship, whether they’re attempts to repair the past or dreams of a fantasized future – often both.

Grief also demands we let go of other attachments, such as places and things – a triage of memory. We go through photographs, books and items of clothing. We lose our family home, or the sense we had of it. Some family traditions are abandoned, others might be adapted.

The tectonic plates of our life are always shifting, but with grief, they quake. Our foundation is shaken, exposing the cracks in ourselves, destabilizing our relationships. If it wasn’t built to last, grief will sweep it away. Only enduring love can outstand death.

Grief turns our world upside down, and sometimes right side up. It offers the gift of truth, the sharp light of clarity. It rearranges our priorities, urging us to live our existence fully, in whatever way is truest to us.

Living fully – or truly – doesn’t mean living in a hurry. On the contrary, it often entails slowing down enough to be fully present. Grief is the reminder that life is a matter of moments – pearls of Now strung together.

My senses are always my guide to the present. Grief can’t be reasoned but it can be expressed.

recently shared a quote by Kyo Maclear which beautifully illuminates this:“Art is an entry point for the difficult. The beautiful is a gateway to the urgent.”

Art comes in many forms and the beautiful is ever-present. Creativity does not need to be grand. The everyday, mundane, small acts – drawing, weaving, cooking, dancing – can become forms of medicine.

This month, I share with you seven creative expressions that have helped me process grief through the senses – see, hear, smell, taste, touch, balance and envision.

With Love,

Sabrina

SEE

Zoe Leonard “Strange Fruit” (for David) | art installation

Philadelphia Museum of Art permanent collection

I have not seen Zoe Leonard’s artwork in person but I was so profoundly moved by its description in Olivia Laing’s book “Lonely City”. For context, Leonard created this work shortly after losing her dear friend, the artist David Wojnarowicz, during the AIDS crisis. I wouldn’t do it justice by paraphrasing, so here is Laing’s poignant description of Leonard’s work:

“Strange Fruit is an installation, completed in 1997 and now part of the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s permanent collection. It’s made from 302 oranges, bananas, grapefruits, lemons and avocados, their content eaten and their torn skins dried before being sutured back together with red, white and yellow thread, embellished with zippers, buttons, sinew, stickers, plastic, wire and fabric. The results are exhibited sometimes together and sometimes in small groupings laid in a state across the gallery floor, where they continue on their implacable business of rotting or shrinking or mouldering away, until in time they will turn to dust and vanish altogether.

In an interview in 1997 with her friend, the art historian Anne Blume, Zoe Leonard talked about how the first fruits came into being:

“It was sort of a way to sew myself back up. I didn’t even realize I was making art when I started doing them…. I was tired of wasting things. Throwing things out all the time. One morning I’d eaten these two oranges, and I just didn’t want to throw the peels away, so absentmindedly I sewed them back up.”

It’s a funny business, threading things together, patching them up with cotton or string. Practical, but also symbolic, a work of the hands and the psyche alike. The use of transitional objects like string could also be a way of acknowledging damage and healing wounds, binding up the self so that contact could be renewed.

Art was a place in which this kind of labour might be attempted, where one could move freely between integration and disintegration, doing the work of mending, the work of grief, preparing oneself for the dangerous, lovely business of intimacy.”

HEAR

Vedran Smailović | music

Listen on YouTube

Beyond personal loss, grief can also be collective. How do we mourn in times of war, climate disasters, or global pandemics? When faced with wide scale tragedy, art can seem irrelevant. Yet creating in response to destruction can also be a radical act, and sometimes the only way to make meaning of the nonsensical.

On May 27th, 1992, a month into the Bosnian War, three shells fell into the middle of the capital of Sarajevo. The grenades exploded among the civilians who were waiting in line for bread on Vaso Miskin Street. 22 people died and more than 70 people were wounded. Cellist Vedran Smailović was at the scene, helping the wounded as best as he could.

The next day, Smailović returned, dressed as he would for a symphony performance, and played Albinoni’s Adagio in G Minor. In the midst of gunshots and grenades, Smailović returned to play his cello for 22 days in honor of the 22 dead.

SMELL

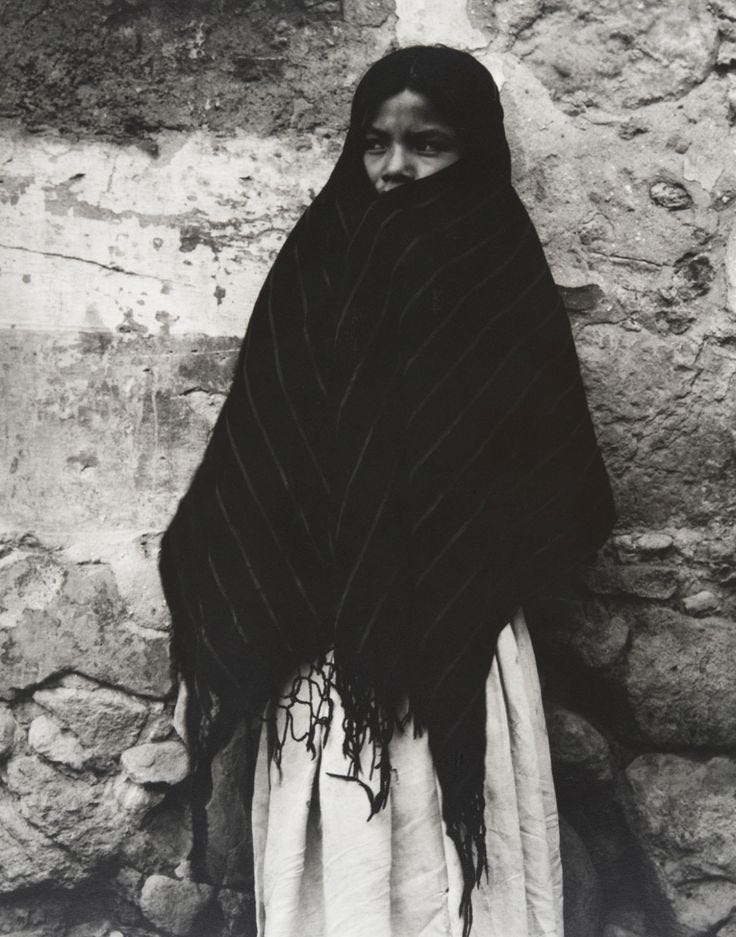

Rebozo de Luto | mourning ritual

Rebozos are traditional Mexican shawls that can be worn as fashion accessories; as sun protectors; or to wrap babies or carry market goods.

The Rebozo de Luto however has a unique function: to acknowledge grief. What makes this rebozo so distinguishable from others is the unique scent it emanates. The tradition is from Tenancingo, a province in central Mexico, where these special perfumed shawls were worn by grieving women as an olfactory comfort and a way to identify the mourners through their fragrance.

Typically the shawl was only worn by first-degree relatives (wife, mother, daughter) shortly after the death of the loved one. The stronger the scent of the shawl, the more recent the death of their loved one. So if you could smell the shawl from across the room, that was a sign this person was in early stages of their mourning and should be treated accordingly. As time passes, the scent would diminish but never completely disappear – an olfactory symbol for the process of grief.

The crafting of the Rebozo de Luto is a laborious and long process. First the cotton textile threads are thoroughly dyed to obtain an intense black color. Then the threads are boiled multiple times, taking care not to burn them, in a special mixture of cascalote plant, rose petals, orange leaf, paxtle, cloves, cacao and water lilies. This is what gives the shawl a special scent, which it retains over the years. Once scented, the threads are dried into the sun before the work of weaving and stitching begins. The entire process can take up to a couple of months.

TASTE

“The Endless Table: Recipes from Departed Loved Ones” | digital cookbook by Ellen Goodman & Michael Hebb

Available online

I recently cooked an old family recipe, which was given to me by my mother and had been passed down to her from my deceased grandmother. All day, while I was prepping in the kitchen, childhood memories of my grandmother resurfaced. Later that night, as my partner and our friends enjoyed the meal, they inquired about the matriarch of my family. It was a rare opportunity to share about my grandmother’s life, her quirks, and most of all the love she showed through her cooking.

Creating moments like this over the dinner table is what motivated the existence of the digital cookbook “The Endless Table: Recipes from Departed Loved Ones.” The stories and recipes were collected and edited by Ellen Goodman of The Conversation Project and Michael Hebb of Death Over Dinner. The book gathers the memories, treasured family recipes and vignettes of personal loss from contributing chefs like Ina Garten, Jose Andres, Tom Colicchio and Christopher Kimball.

Beyond the food, Goodman and Hebb wanted their cookbook to encourage people to have end-of-life discussions with their loved ones before it’s too late. Goodman explains:

“For some, talking about death is like letting it in the room. The end of life isn’t just a medical thing that happens, it’s a human experience. People aren’t dying the way they want to or having their wishes honored…so having a conversation like this is a gift you give your family.”

To make things easier, the cookbook also contains a guide on how to approach talking about end-of-life wishes, compiled using advice from both health experts and families.

TOUCH

Marma Massage | Ayurvedic treatment

One of the most touching gestures I recently received came from my friend Lila. Upon learning of my dad’s passing, she offered to give me a Marma massage. Receiving healing touch and deep presence turned out to be some of the most valuable gifts during this time of grief.

The particular massage technique stems from India’s ancient healing science - Ayurveda. Ayurveda describes 72,000 channels in the body that facilitate the movement of vital energies (electric signals, hormones, blood, lymphatic fluid, etc) and allow communication between systems - from the cellular level to the body as a whole.

Marma refers to “vital” points, which connect the subtle nerves (nadis) and the energetic centers (chakras). Toxins, stress and negative emotions often get lodged at marma sites, and can lead to physical and mental disease. Working on these vital points unblocks the flow of energy to rebalance our life force (prana).

The massage takes between 90 minutes to three hours. It includes several stages which involve stretching the muscles, applying pressure using various tools, even lightly walking on the body. It ends with an oil massage, with special attention given to the feet and head. Not all stages feel blissful, but healing can often involve a measure of discomfort. Breathing in sync with the movements helped me through some tender spots. By the end of the massage, I felt both lighter and more grounded.

Lila and her husband Yamouna, an ayurvedic practitioner, are based in Los Angeles and offer Marma treatments as well as Marma training workshops, which you can learn more about on Jivana Wellness.

BALANCE

Mourning Surf | movement for grief

I learned so much about loss and mourning while working with my client J’aime Morrison, the founder of Mourning Surf. She offers a different approach to grief, which I’ve been personally applying lately.

J’aime is a life-long dancer, who earned her PhD in Dance from NYU and went on to choreograph and teach in Los Angeles. Dance and movement have always been part of her life but when she lost her husband, she found movement expression to be crucial to her grief process.

While grief support groups and talk therapy was helpful, she realized that something was missing – her physical experience wasn’t addressed. Yet studies have shown that grief can affect the immune system, cause inflammation, and may even worsen pre-existing conditions. Grief is both an emotional and physical state.

In 2020, J’aime started guiding movement-for-grief workshops for other widows. Since then, she’s launched Mourning Surf, offering virtual and in-person grief workshops and retreats.

Yesterday I was able to experience my first movement-for-grief workshop, titled “Mapping Grief in the Body: A Guided Movement Meditation.” After a short introduction of the work, J’aime first guided us through a body-scan meditation. Then through seated and standing poses, we moved together through intuitive and simple gestures. We paid attention to where grief showed up as pain and tension in our body. At the end, we each contributed one movement to create a collective sequence - a sort of grief choreography. By the end, I felt grounded and connected with a group of strangers by simply moving in synch through our grief.

J’aime will be hosting another grief retreat this summer in Costa Rica, which you can learn more about here: TwoCan Retreats x Mourning Surf.

ENVISION

Photography | Kenshō studio

I thought about creating a video poem on grief. I envisioned a film montage of old photographs and clips of my father. I even considered recording part of my eulogy. But it all seemed unsurmountable. Neither art nor grief can be rushed.

Both come unexpectedly, and take unlikely shape. This time, it was a photograph. Taken recently in Mexico City, this moment captures grief to me: both somber and hopeful, simple and transcendent – an opening between here and beyond.

This is beautiful Sabrina. I am sending so much love and energy for all of these up and down waves and the massive in between space that's in the "before" and "after." Three years ago I lost two people who were basically my second parents in a very tragic way, so a lot of this resonates for me. "Creativity does not need to be grand. The everyday, mundane, small acts – drawing, weaving, cooking, dancing – can become forms of medicine." I love this, and I also think that grief can manifest like that too - it doesn't always show up in the huge debilitating ways like we might expect, often it's as you put it, discombobulating. Thank you for sharing your words and may your own creative acts, whether they be big or small, create a sense of tethering for you. ❤️

Dear Sabrina, this probably is a masterpiece spurted out of your creative meridian that in crisis becomes a vital component which helps us process our grief. Your words are honest and raw drenched in yearnings and insights. I am still struggling with my father’s cancer journey and nothing has spoken to me of the reality of death as deeply as this piece.

Even if I arrived here late, I’m sending you a warm virtual hug. I know, I just do. Thank you for writing this.